YOU NEED NEVER PAY ANOTHER DIME IN INCOME TAXES

The Supreme Court has already ruled that:

• The government's present method of collecting income taxes is unconstitutional.

• Wages, rents, dividends, and interest are not income.

• Income can only be a corporate profit.

That is why there are no laws requiring anyone to:

• File income tax returns.

• Pay income taxes, or

• Submit to IRS audits.

Learn the facts and discover why the Federal

income tax is a gigantic hoax and why

millions of law abiding, patriotic Americans

no longer pay this illegal and destructive tax.

Freedom Books . 544 East Sahara Blvd. . Las Vegas, NV 39104

$17.95

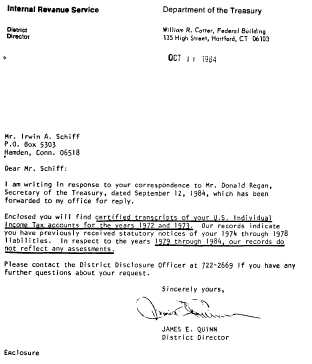

In THE GREAT INCOME TAX HOAX, Irwin Schiff- the nation's leading tax expert - proves that for over seventy years the government has been ILLEGALLY collecting income taxes. While staggering, the implications in Schiff s expose are nonetheless true. You will discover that the Federal government itself is the nation's most prolific lawbreaker; confiscating property without statutory authority and jailing people for tax crimes that do not exist.

For example, did you know that the Supreme Court has ruled that:

1. The income tax is unconstitutional as currently enforced?

2. The 16th Amendment did not amend the Constitution?

3. Rents, dividends, and interest are not "income" and you do not have to pay any "income" taxes on such items?

4. The only "income" subject to income taxes is corporate profit - so if you do not have a corporate profit you cannot be subject to an "income" tax? (Even corporations, however, are not subject to the current income tax.)

5. According to the Supreme Court's official definition of "income," wages are not subject to taxation as "income" under our laws?

6. There is no law that says you can be "liable" for Federal income taxes or that your are "required" to pay them?

You can stop rubbing your eyes in disbelief since all of the above is true -including the fact that the entire Federal judiciary is in on the swindle and is knowingly breaking the law!

Schiff supports his claims with extensive excerpts from every important Supreme Court case bearing on the income tax and from the Internal Revenue Code itself. His book is probably the most extensively researched and documented book that has ever been written about Federal income taxes. It proves that the whole system is a gigantic legal hoax and that THE FEDERAL JUDICIARY KNOWINGLY PUTS PEOPLE IN JAIL WHEN THEIR ONLY CRIME IS THAT THEY KNOW THE LAW AND ARE NOT TAKEN IN BY THIS HOAX.

Schiff does not simply make naked charges. He substantiates each and every statement he makes. He proves that the entire Federal "court" system, from district court up to Supreme Court itself, is in on this hoax. He also proves that in order to illegally collect income taxes the Federal Government, with the help of the "courts," has managed to throw out the entire Bill of Rights along with every constitutional provision that limited the Federal Government's taxing powers. In addition, extensive appendix material includes a expose of the illegal nature of all U.S. coin and currency.

Schiffs book not only provides the reader with a comprehensive understanding of the income tax, it also describes the constitutional basis of Federal power and how it is abused in various other areas. While it deals primarily with taxes

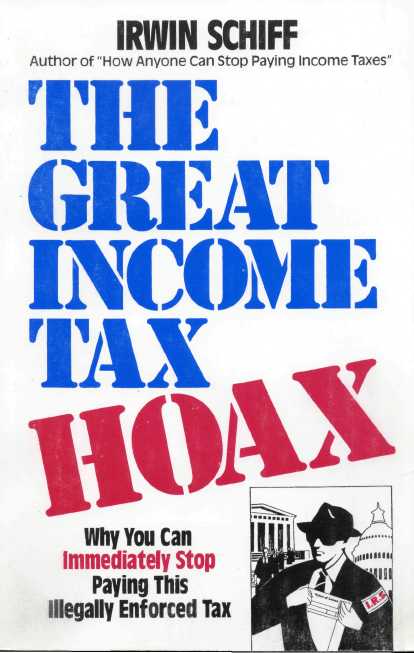

THE GREAT

mum* i \x HOAX

Freedom Law School

9582 But*,mere Road xL^ Phelan, C/\ 92371

ÂŁT (760) 868-4271

ll-v \vw\v.livcfrecnow.org

^•'i'?^ frecdorn@livefrcenow.org

Irwin Sctaif f

HIE GREAT INCOME XIX

HOAX

Why You Can immediately Stop Paying This Illegally Enforced Tax

jfreebom poote

544 East Sahara Blvd

Las Vegas, NV 89104

visit our website at: www.paynoincometax.com

This book is designed to provide the author's findings and opinions based on research and analysis of the subject matter covered. This information is not provided for purposes of rendering legal or other professional services, which can only be provided by knowledgeable professionals on a fee basis.

Further, there is always an element of risk in standing up for one's lawful rights in the face of an oppressive taxing authority backed by a biased judiciary.

Therefore, the author and publisher disclaim any responsibility for any liability of loss incurred as a consequence of the use and application, either directly or indirectly, of any advice or information presented herein.

Sections of the Internal Revenue Code reprinted by permission from the Tax and Professional Services Division, The Research Institute of America, Inc. Copyright ©1984.

Copyright© 1985 by Irwin A. Schiff

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 85-070036

ISBN-0-930374-05-3 nn nn n i m m s <i •? i i

TO

Melville Weston Fuller, Chief Justice of the United States from 1888-1910, and Stephen Johnson Field, Associate Supreme Court Justice from 1863—1897, for the judicial integrity they displayed in holding an income tax unconstitutional; and for their magnificent opinions which, by contrast, clearly reveal the criminal nature of today's Federal judiciary.

BOOKS BY IRWIN SCHIFF

The Federal Mafia — How It Illegally Imposes and Unlawfully Collects Income Taxes —

The Great Income Tax Hoax How An Economy Grows and Why It Doesn't

The Social Security Swindle — How Anyone Can Drop Out —

How Anyone Can Stop Paying Income Taxes

The Kingdom ofMoltz The Biggest Con: How the Government Is Fleecing You

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION..................................................... 9

1. Direct vs Indirect Taxes............................................. 11

2. Constitutional Restrictions Regarding

Direct And Indirect Taxes........................................ 19

3. The Intent Of The Constitution................,................... 25

4. The Federal Government's General

Taxing Powers...................................................... 31

5. What The U.S. Government And America

Are All About....................................................... 39

6. Federal Real Estate Taxes — How They

Were Levied and Collected....................................... 55

7. The Civil War: The Seeds Of Tax

Tyranny Are Sown................................................. 67

8. The Supreme Court Declares an Income

Tax Unconstitutional..........................................__ 77

9. The Agitation For The Income

Tax: 1895-1909..................................................... 123

10. The Corporation Excise Tax of 1909 ............................... 131

11. The Sixteenth Amendment.......................................... 149

12. Surprise! The Income Tax Is An Excise

Tax: The Brushaber Decision .................................... 181

13. Income —What Is It?................................................ 205

14. Why No One Can Have Taxable Income........................... 223

15. Income Tax "Laws" and How The IRS

Disregards Them .................................................. 239

16. TheFederal"Judiciary" ............................................. 263

17. Tax "Court" and Other Tax-Related Scams....................... 295

18. HOW TO END THE INCOME TAX NOW!.................... 377

Appendix A: The Total American Tax Take.............................................................409

Appendix B: The Elliot Debates ....................................413

Appendix C: 18th and 19th Century Federal Tax Statutes ..............................................439

Appendix D: Brief Supporting Contention That Wages Are Not Income ................................461

Appendix E: Briefs Exposing Government's Illegal Monetary Policies.................................479

Appendix F: Miscellaneous Correspondence and "Court" Decisions.................................523

Reference Materials: Books, Reports

and Tapes by Irwin Schiff........................................ 555

INDEX..................................................................559

INTRODUCTION

This book will shock you. It will convince you that for over seventy years the Federal government has been illegally collecting income taxes and that the courts (if not Congress) know it. Federal judges allow property to be illegally confiscated and knowingly send innocent people to jail in order to intimidate an uninformed public and to aid the IRS in illegally enforcing Federal tax law. The reason the public can be duped and intimidated is because it does not know the law or even the legal meaning of income. Most Americans do not realize they have no income that can be legally taxed under our income tax laws.

This book will clearly explain the law to you so that you will know why you can legally stop paying income taxes immediately and how you can protect yourself from IRS harrassment and control.

In essence, history has repeated itself and America now finds itself in the same circumstances as Thirteenth Century Egypt. In the Twelfth Century, slaves known as Mamelukes (literally "owned men") were brought to Egypt to serve as soldiers to the Sultan. In 1250 they overthrew the government they were supposed to serve, installed one of their own as Sultan and ruled Egypt for the next two hundred and fifty years. America has essentially the same problem.

The Federal government was created (with limited power) by the people of America in order to protect their unalienable rights to life, liberty, and property. Federal employees were recruited and sent to Washington to administer the laws commensurate with this limited grant of power. Initially, these employees were conceived as servants of the people; however, as the Mamelukes before them, the Federal bureaucracy has now illegally installed itself as the master while the people have become their servants.

In order to manage this, America's Mamelukes had to destroy the very document designed to limit their power and keep them in check. This was largely achieved by those assigned the role of "judges!" In addition, the key ingredient in the expansion and preservation of Mameluke control of America has been their success in installing and illegally enforcing the income tax.

Many Americans are now united in a struggle to depose American Mamelukes and to retrieve and reestablish both the document and the freedoms they have destroyed. The days of Mameluke control of America are numbered. More and more Americans are learning to recognize our

Mamelukes for the usurpers they are. They are learning how to successfully fight them. This book was written to help in that struggle and to persuade you to join the battle. The faster we get rid of our Mameluke masters and their illegal income tax the better off we will all be.

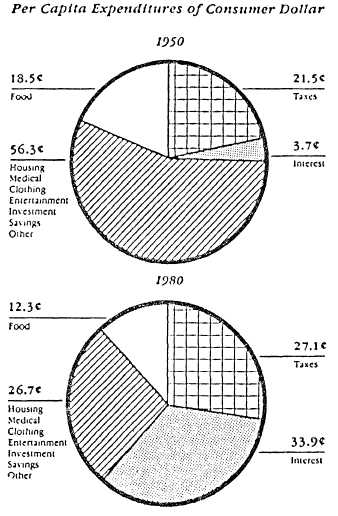

Not only is the battle to free America from Mameluke control exciting, it will also allow you to have more money to spend while enjoying life, your new-found liberty, and your increased ability to pursue your own happiness. According to the April, 1983 issue of Life magazine some 20,000,000 working Americans have stopped filing income tax returns — WE NOW HAVE THE MAMELUKES ON THE RUN!

1

Direct vs Indirect Taxes

In an 1819 decision Chief Justice John Marshall wrote: "The power to tax involves the power to destroy!' History agrees. From the beginning of organized government, kings and ruling castes used taxation as an instrument and a weapon. Throughout recorded history, moreover, capricious or heavy-handed taxation led to insurrection or, less dramatically, to the dissolution of the ties which bind people to their government. In Twelfth Century England, outrageous taxation inspired the Peasants' Revolt which rampaged until Richard II skewered the head of Wat Tyler, its leader, on a pole. It was the very issue of taxes that sparked the American Revolution and today the tax system in America is as vi-olative of the rule of law and the Constitution as the "judges" who administer it.

In ancient times, kings and emperors needed taxes for the support of their courts and armies. Men-at-arms and the nobility produced no wealth so they had to be supported by those who did. Historically, governments have been run by non-producers and non-producers generally gravitate to government service. But to the extent that government performs its limited social function — that of protecting society from external enemies and maintaining internal peace and order by eliminating social predators — the cost of supporting government workers can be born out of the increased productivity that a limited, well-run government will generate.

The first 150 years of America bears excellent testimony to this principle. Unfortunately, history demonstrates the accuracy of Lord Acton's observation that "power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely!' As government acquires more power1 it becomes arbitrary and corrupt. Taxes are increasingly raised for the support of entrenched government, not for the benefit of society. Eventually, the growing army

1 In America this unconstitutional expansion of federal power was achieved by the government, illegally maintaining and exercising (in peacetime) numerous emergency powers it acquired as "temporary" war-time measures.

of government created non-producers will no longer be able to be supported by the ever dwindling number of producers and the economic and social structure of society will ultimately give way.

This is the story of Rome and provides the explanation for what is happening in America today. The parallel between the decline of Rome and the decline of America is so sharp that only government-run schools could fail to make the connection.

Only People Pay Taxes

How should government extract taxes? Citizens could be required to pay a certain sum to the "royal" tax collector—but how much? Since some citizens can afford to pay more than others, governments devised methods for taxing citizens according to their supposed ability to pay or, in simpler terms, according to their wealth which became one of the earliest forms of taxation. However, while such taxes appear to tax wealth, it is the citizen that is being taxed, not his wealth. He is being taxed according to his wealth. It is important to keep this distinction in mind. As you will see, the government seeks to fool the public on this simple issue. For example, property taxes are not really taxes on property but taxes on individuals based on the property they own. All such taxes fall within the constitutional category of "direct taxes."

The Importance of Tax Classes

The Constitution recognizes two classes of taxes and imposes different restrictions on the Federal government's right and ability to impose either. It is important, therefore, that the taxpayer be able to identify both classes in order to determine whether they are being levied constitutionally. The government and the courts have evaded the issue by claiming that the differences between the two taxing categories are unclear — that the Founding Fathers (who were so specific in everything else) did not know what they were talking about and that their proscriptions on the power of taxation were the result of confusion and lack of clear thinking. This is self-serving nonsense. The courts know, as we all do, what great texts the Founding Fathers consulted, what they were influenced by, and how they debated the system they embodied in the Constitution. Not only were the framers of the Constitution keenly cognizant of the issues before them, they also had studied Adam Smith's definitive work, The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776 — the same year the Declaration of Independence was written. I will quote extensively from this material so there can be no doubt in anyone's mind

regarding exactly what the Founding Fathers had in mind when they wrote these taxing restrictions into the Constitution.

Capitation Taxes

The first category of taxes taken up in the Constitution were "capitation and direct taxes." This is what Smith had to say about them.

Capitation taxes, if it is attempted to proportion them to the fortune or revenue of each contributor, become altogether arbitrary. The state of a man's fortune varies from day to day, and without an inquisition more intolerable than any tax, and renewed at least once every year, can only be guessed at. His assessment, therefore, must in most cases depend upon the good or bad humour of his assessors, and must, therefore, be altogether arbitrary and uncertain.

Capitation taxes, if they are proportioned not to the supposed fortune, but to the rank of each contributor, become altogether unequal; the degree of fortune being frequently unequal in the same degree of rank.

Such taxes, therefore, if it is attempted to render them equal, become altogether arbitrary and uncertain; and if it is attempted to render them certain and not arbitrary, become altogether unequal. Let the tax be light or heavy, uncertainty is always a great grievance. In a light tax a considerable degree of inequality may be supported; in a heavy one it is altogether intolerable.

In the different poll-taxes which took place in England during the reign of William III. the contributors were, the greater part of them, assessed according to the degree of their rank; as dukes, marquisses, earls, viscounts, barons, esquires, gentlemen, the eldest and youngest sons of peers, etc. All shopkeepers and tradesmen worth more than three hundred pounds, that is, the better sort of them, were subject to the same assessment, how great soever might be the difference in their fortunes. Their rank was more considered than their fortune. Several of those who in the first poll-tax were rated according to their supposed fortune, were afterwards rated according to their rank. Serjeants, attornies, and proctors at law, who in the first poll-tax were assessed at three shillings in the pound of their supposed income were afterwards assessed as gentlemen. In the assessment of a tax which was not very heavy, a considerable degree of inequality had been found less insupportable than any degree of uncertainty.

In the capitation which has been levied in France without any interruption since the beginning of the present century, the highest orders of people are rated according to their rank, by an invariable tariff; the lower orders of people, according to what is supposed to be their fortune, by an assessment which varies from year to year. The officers of the king's court, the judges and other officers in the superior courts of justice, the officers

of the troops, etc. are assessed in the first manner. The inferior ranks of people in the provinces are assessed in the second. In France the great easily submit to a considerable degree of inequality in a tax which, so far as it affects them, is not a very heavy one; but could not brook the arbitrary assessment of an intendant. The inferior ranks of people must, in that country, suffer patiently the usage which their superiors think proper to give them.

In England the different poll-taxes never produced the sum which had been expected from them, or which, it was supposed, they might have produced, had they been exactly levied. In France the capitation always produces the sum expected from it. The mild government of England, when it assessed the different ranks of people to the poll-tax, contented itself with what that assessment happened to produce; and required no compensation for the loss which the state might sustain either by those who could not pay, or by those who would not pay (for there were many such), and who, by the indulgent execution of the law, were not forced to pay. The more severe government of France assesses upon each generality a certain sum, which the intendant must find as he can. If any province complains of being assessed too high, it may, in the assessment of next year, obtain an abatement proportioned to the overcharge of the year before. But it must pay in the mean time. The intendant, in order to be sure of finding the sum assessed upon his generality, was impowered to assess it in a larger sum, that the failure or inability of some of the contributors might be compensated by the over-charge of the rest; and till 1765, the fixation of this surplus assessment was left altogether to his discretion. In that year indeed the council assumed this power to itself. In the capitation of the provinces, it is observed by the perfectly well-informed author of the Memoirs upon the impositions in France, the proportion which falls upon the nobility, and upon those whose privileges exempt them from the taille, is the least considerable. The largest falls upon those subject to the taille, who are assessed to the capitation at so much a pound of what they pay to that other tax.

Capitation taxes, so far as they are levied upon the lower ranks of people, are direct taxes upon the wages of labour and are attended with all the inconveniencies of such taxes.

Capitation taxes are levied at little expence; and, where they are rigorously exacted, afford a very sure revenue to the state. It is upon this account that in countries where the ease, comfort, and security of the inferior ranks of people are little attended to, capitation taxes are very common. It is in general, however, but a small part of the public revenue, which, in a great empire, has ever been drawn from such taxes; and the greatest sum which they have ever afforded, might always have been found in some other way much more convenient to the people. (Emphasis added)

Examples of Capitation And Direct Taxes

As explained by Adam Smith there are a variety of capitation taxes2 and each can be levied according to different criteria: wealth, revenue, rank, occupation or even "upon the wages of labor!' Note that Smith (whose ideas were a major guide to the framers of the Constitution) stated that capitation taxes attempted to "proportion" taxes to either the fortune or the revenue of each contributor!' He made it absolutely clear that taxes related to income were direct taxes which is extremely relevant since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that an income tax was not a capitation tax on the absurd claim that "Smith's work as to the meaning of such a tax" made no distinction between direct and indirect taxes (see page 105). This claim was patently false since Smith not only made a definitive distinction he also specifically labelled taxes related to income as being capitation or direct taxes!

There is no question that an income tax is clearly a capitation tax whereby the government seeks to tax individuals directly according to their income. It is important to remember, however, that in all capitation taxes (perhaps they should have been called decapitation taxes) it is not wealth, revenue, rank, or occupations that are being taxed but the individual — and he is being taxed according to some arbitrary yardstick the government believes measures his ability to pay. If you think an "income" tax is a tax on "income" then let your "income" calculate and pay the tax! Instead of taxing you according to your income, the government could conceivably tax you according to your weight, say at $1.00 per pound. Someone who weighs one hundred pounds would pay a $100.00 "weight tax" and someone who weighs two hundred pounds would pay $200.00. But would such a tax actually be a tax on "weight"? No, it would be a tax on the individual measured by his weight. For the same reason an "income" tax is not a tax on "income" — it is a tax on the individual measured by his "income."

Taxing People Directly

If a government decides to tax people directly according to their wealth, there remains the problem of how to determine that wealth. Will citizens be compelled to disclose the amount and nature of what they possess to the tax collector so they can be properly taxed? Under

3 Note that Smith uses "poll" and "capitation" taxes interchangeably and says that either can relate to rank or fortune.

the Constitution, citizens cannot be compelled to provide information that can be used against them and they are further presumed to have a right to privacy. Yet all information on a tax return can be used against taxpayers — and can even be given to other Federal agencies as well as to state and foreign governments to be used against them. Exactly how much privacy does a citizen have after giving all the information required on a 1040?3 Requiring Americans to file income tax returns violates the First and Ninth Amendments which is why (though few people seem to know this) no such filing requirement is contained in the law.

In England, direct taxes were once levied on chimneys and windows, the theory being that the more windows and chimneys a house had the wealthier the owner and the more taxes he could pay. Again, the tax was not actually on windows or chimneys but was, rather, on the individual who owned the home measured by the number of chimneys and windows he had (which presumably measured his ability to pay). In The Wealth of Nations Adam Smith gives an interesting description of how such taxes worked.

The contrivers of the several taxes which in England have, at different times, been imposed upon houses, seem to have imagined that there was some great difficulty in ascertaining, with tolerable exactness, what was the real rent of every house. They have regulated their taxes, therefore, according to some more obvious circumstance, such as they had probably imagined would, in most cases, bear some proportion to the rent.

The first tax of this kind was hearth-money; or a tax of two shillings upon every hearth. In order to ascertain how many hearths were in the house, it was necessary that the tax-gatherer should enter every room in it. This odious visit rendered the tax odious. Soon after the revolution, therefore, it was abolished as a badge of slavery.

The next tax of this kind was, a tax of two shillings upon every dwelling house inhabited. A house with ten windows to pay four shillings more. A house with twenty windows and upwards to pay eight shillings. This tax was afterwards so far altered, that houses with twenty windows, and with less than thirty, were ordered to pay ten shillings, and those with thirty windows and upwards to pay twenty shillings. The number of windows can, in most cases, be counted from the outside, and, in all cases, without entering every room in the house. The visit of the tax-gatherer, therefore, was less offensive in this tax than in the hearth-money.

This tax was afterwards repealed, and in the room of it was established the window-tax, which has undergone too several alterations and

8 The full details on this can be found in How A nyone Can Stop Paying Income Taxes by Irwin Schiff (FREEDOM BOOKS: 1982).

augmentations. The window-tax, as it stands at present (January, 1775), over and above the duty of three shillings upon every house in England, and of one shilling upon every house in Scotland, lays a duty upon every window, which, in England, augments gradually from two-pence, the lowest rate, upon houses with not more than seven windows; to two shillings, the highest rate, upon houses with twenty-five windows and upwards.

The principal objection to all such taxes is their inequality, an inequality of the worst kind, as they must frequently fall much heavier upon the poor than upon the rich. A house often pounds rent in a country town may sometimes have more windows than a house of five hundred pounds rent in London; and though the inhabitant of the former is likely to be a much poorer man than that of the latter, yet so far as his contribution is regulated by the window-tax, he must contribute more to the support of the state. (Emphasis added)

In Eighteenth Century England, the fact that tax collectors could enter one's home to count the hearths was considered such an "odious visit" that the tax was abolished as "a badge of slavery!' If such a visit was a "badge of slavery," how much more odious is a visit today from the IRS to search a taxpayer's papers, books, and private records — in clear violation of the Fourth Amendment — and to make them prove every expenditure?

In the final analysis, for any government to tax directly, it must first find the individual in order to tax him/her — regardless of what yardstick (wealth, income, rank, occupation, etc.) is used. Governments, however, have discovered another way to tax individuals without having to catch them, or without even knowing they exist which leads us to the other category of taxes provided for in the Constitution.

Indirect Tbxes

Since individuals use a variety of products, governments have discovered another, easier way to levy taxes—by putting taxes on the products they buy. The more a person buys, the more taxes he pays. Such taxes are not paid directly to the government; they are paid indirectly through the merchants who sell the products. Indirect taxes are relatively easy to levy and collect and are placed on products as they are produced within a country or imported. The manufacturer or importer pays such "excises" or "duties" and adds them to the price of the product, thus passing the tax on to the consumer.

An important distinction between indirect taxes and capitation (direct) taxes is that indirect taxes are avoidable. If the individual does not buy the taxed products he avoids paying the taxes imposed. Capitation taxes, on the other hand, are not avoidable since they are levied

directly on the individual. Since direct taxes are not avoidable they are subject to far greater tyrannical abuse than indirect taxes — which is why the Constitution makes them subject to special conditions not applicable to indirect taxes.

The following passage fromThe Wealth of Nations will provide a clear understanding of the meaning of indirect taxes as understood by those who wrote our Constitution.

The impossibility of taxing the people, in proportion to their revenue, by any capitation, seems to have given occasion to the invention of taxes upon consumable commodities. The state not knowing how to tax, directly and proportionably, the revenue of its subjects, endeavours to tax it indirectly by taxing their expence, which, it is supposed, will in most cases be nearly in proportion to their revenue. Their expence is taxed by taxing the consumable commodities upon which it is laid out. (Emphasis added)

Note that Smith makes as clear a distinction as can be made that taxing people "in proportion to their revenue" is clearly a type of capitation tax as opposed to the taxes on "consumable commodities" which obviously fall into the category of indirect (excise) taxes. Here his statement clearly proves that the numerous claims by U.S. judges that "income" taxes are not capitation taxes (falling, rather, within the category of excise taxes) have been a cynical perversion of logic and law.

Government Now Fools The Public

It is crucial that the American public rediscover the distinction between direct and indirect taxes because the Constitution lays down different provisions regarding how each is to be lawfully levied. The Federal government (with the help of a perfidious Federal judiciary) now completely disregards these constitutional distinctions and is, therefore, able to collect taxes in a blatantly illegal manner.

2

Constitutional Restrictions

Regarding Direct And

Indirect Taxes

The Constitutional provision regarding how indirect taxes are to be levied is found in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 1, of the Constitution and also defines the Federal government's general taxing powers:

... Congress shall have the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States; but all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States. . . (Emphasis added)

Note that in the first portion of this paragraph Congress is given the power to lay: a) taxes, b) duties, c) imposts and d) excises but the word "taxes" is later deliberately omitted from the requirement that all such listed taxes be "uniform throughout the United States!' Only "duties, imposts and excises" were made subject to the requirement that they be uniform throughout the United States. Why? The reason the word "taxes" was specifically omitted from the latter phrase, is because the Constitution already provided (in Article 1, Section 2) for a different method of levying "taxes" which, in colonial times, generally meant direct taxes. So Article 1, Section 8 only sought to establish a constitutional method for levy ing "duties, ""imposts, "and "excises, "all of which are indirect taxes, since other sections of the Constitution provided the legal basis by which direct taxes were to be levied.

So, for excises, imposts and duties to be constitutional, they have to be levied on the basis of uniformity, while direct taxes must be levied according to another standard. Uniformity means that if the government levies a tax of 10$ on a pack of cigarettes, the tax must apply equally to cigarettes manufactured in every state. It would be uncon-

stitutional for the government to levy an excise or duty on a product in one state but exclude certain manufacturers or importers in other states from the same duty or tax. The government, however, can discriminate between products when imposing excises and import duties. It can tax one product and not another, or one type of manufacturer and not another. As long as all similar manufacturers and similar products are equally taxed in all states, the tax is uniform and, therefore, constitutional.

Direct Taxes Are To Be Apportioned

Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution says:

... Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective numbers. . . (Emphasis added)

This requirement of apportionment of direct taxes is repeated in Article 1, Section 9, Clause 4 as follows:

... No capitation, or other direct tax shall be laid unless in proportion to the census or enumeration herein before directed to be taken. (Emphasis added)

The "herein before directed to be taken" refers to the prior reference contained in Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3.

Though not dealing directly with taxation, The Bill of Rights further protected citizens from the arbitrary use of taxing power. For example, the Fourth Amendment guaranteed that the right of the people to be "secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects ... shall not be violated" and that any searches and seizures must be supported by "oath or affirmation" and be court ordered only "upon probable cause!' And the Fifth Amendment guaranteed that: "... no person shall be held to answer" for an infamous1 crime "unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury ... nor shall he be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation." (Emphasis added in both quotes.) Today these constitutional guarantees are totally ignored by the "courts" and the IRS. Individuals are put to trial for tax "crimes" without indictments and without any probable cause being established; are jailed for refusing to turn over "papers and effects" to the IRS and

1 The Supreme Court has ruled that an "infamous crime" is one punishable by imprisonment. Exparte Wilson 114 US 417, Mackin vs US 117 US 348.

for refusing (in tax matters) to be "witnesses against themselves"; and are routinely deprived of property without "due process of law!'

\bu will note that the Founding Fathers, unlike Smith, drew a distinction between capitation taxes and all other direct taxes. This was because they regarded capitation taxes as direct taxes levied specifically on people (and therefore particularly abhorent because they could be levied arbitrarily), as opposed to other forms of direct taxes levied on property (both real and personal). In either case, people pay the tax directly to the government and, as such, both are (by definition) direct taxes. Therefore, though (in a constitutional sense) a capitation is a direct tax, not all direct taxes are capitations.

Apportionment

The requirement of apportionment of direct taxes is the only provision in the Constitution stated twice. It was written into the Constitution only after extensive debate and probably represents the most important compromise of the entire Constitutional Convention, and their inclusion most likely created more controversy and debate at the state ratifying conventions than any other provision. No less than five states recommended in their ratifying statements that these two provisions should be removed and the Federal government's direct taxing power be eliminated entirely. %t today these two provisions (though their force is still as undiminished and binding as the day they were written) are totally ignored by the U.S. government — as if the limitations imposed upon the government by them did not exist at all!

In contrast to excises, imposts, and duties (indirect taxes), the Constitution requires that all capitation and other direct taxes be "apportioned among the states" (according to population) as opposed to the principle of uniformity. This means that for a Federal direct tax to be lawful it must be levied so that the total tax collected from the residents of each state must be proportional to each state's population (in that the amount collected from each state must bear the same proportion to the total tax as that state's population bears to the nation's total population). If any Federal direct tax is not levied in this manner it is unconstitutional and, therefore, illegal!

How Apportionment Works

The state of Arkansas has a population roughly equivalent to 1% of the nation so its citizens must (constitutionally) pay 1% of any direct tax imposed by the Federal government. If the Federal government imposes a direct tax (based on "income," for example) of $100 billion, the citizens of Arkansas must (collectively) pay $1 billion of that tax.

Californians, on the other hand, constitute 10% of the nation and would, therefore, have to (collectively) pay $10 billion of such a tax. As you see, another important distinction between direct and indirect taxes is that before direct taxes can be lawfully extracted (on a compulsory basis) the total amount to be extracted must be exactly determined beforehand so that the correct apportionment can be made. The amount to be collected by indirect taxes, on the other hand, does not have to be predetermined but can be imposed to generate whatever revenue they can bring in.

Based on the 1970 census, California had forty-three representatives in Congress and Arkansas had four. Californians would, therefore, have to pay ten times as much of any direct Federal tax as do the people of Arkansas. If they did this they would be paying the tax in direct proportion to their representation in Congress (as required by Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution). As I stated previously, if any Federal direct tax is not imposed in this specific manner, it is imposed unconstitutionally and no American need take any notice of it.2 Since the concept of apportionment is so crucial for an understanding of the Federal government's legitimate taxing powers (and since this principle is practically unknown today — let alone understood), we should nail it down even further.

If two states have the same population then citizens of both states have to (collectively) pay the same total amount of any direct Federal tax. If the tax concerned property (the Federal government can tax property, see Chapter 6), and if State A had half the amount of taxable property as did State B, the Federal property tax rate in State A would have to be twice as high as that in State B in order for both states to generate the same total Federal property tax. If the tax concerned "income" — and the citizens of State A have half the taxable income as those of State B — then the Federal income tax rates in State A have to be twice as high as those in State B in order, again, for both states to generate the same total "income" tax revenue. On the basis of population, since both states are represented equally in Congress, both states have to pay the same (equal) amount of any direct tax, making taxation and representation directly proportional — on a state-to-state basis!3

1A fundamental principle of American law is "...anything repugnant to the Constitution is null and void..." This principle was laid down by John Marshall in Marbury vs Madison 1CR 137, and means that all citizens are free to disregard all Federal "laws" promulgated in obvious disregard of the Constitution. Such "laws" are, in reality, not laws at all but are born dead.

8 A state's taxing power, for example, is not limited by any such consideration, though no state can lawfully compel payment of state income taxes for a variety of other reasons!

A Compulsory Income Tax Must Be Related To State Population

Since the income tax is currently levied as a direct tax it must be based on state population. Since it is not, the tax is collected in a totally unconstitutional manner. When direct taxation was linked to state population and representation in Congress, a fundamental principle of the American Revolution ("taxation without representation is tyranny") was preserved and consciously incorporated into the U.S. Constitution. The Federal government, however, illegally destroyed this principle and that linkage (when it realized that the American public did not understand, nor was even aware of it) and, in so doing, completely destroyed the "federal" character of the American Republic. Tying direct taxation to state representation is, essentially, what Federalism is all about. Destroy that linkage and you no longer have a Federal republic.4

America — No Longer A Federal Republic

The Federal establishment succeeded in engineering this fundamental change in the nature of our country with the help of a lawless Federal judiciary5 that is itself a part of that establishment. Federal employees thus increased their own power by illegally converting America from what started out as a democratic, federal republic into what we now have, which is essentially a centralized democracy — a form of government never imagined, conceived, or contemplated by the framers of the Constitution. Such a form of government was, in fact, abhorent to and feared by them (see pages 43,44). For this reason, we should never, logically, refer to the nation's government as the "Federal" government since what we now have is a monolithic central government with almost no remaining constitutional checks and balances.6

4 For a practical example of how this works, see Chapter 6.

6 Someone once defined a judge as a lawyer who knew a governor. I believe this is accurate and helps explain the sorry state of our judicial system.

6 To the extent that I use the term "Federal government" I do so reluctantly and only because of style and clarity. But the term itself has ceased to have any meaning.

3

The Intent Of The Constitution

To determine whether our understanding of the government's con-situtional taxing powers is indeed correct, we need only refer to the pub-lished statements of those who wrote and ratified that document. One of the most authoritative works, The Federalist Papers, contains a collection of essays written by three of the most knowledgeable and influential men of their day: Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay. Hamilton served as our first Secretary of Treasury and was one of the most indefatigable workers on behalf of ratification. If not for the efforts and energy expended by Alexander Hamilton, the Constitution may never have been ratified. James Madison is, of course, regarded as the "Father of the Constitution" while John Jay served as the nation's first Chief Justice and presided over a number of sessions of the Constitutional Convention.

This towering triumverate combined to write The Federalist Papers (actually a series of essays that first appeared in New York newspapers between October, 1787 and March, 1788, written to rally public support for the proposed Constitution in a state where considerable opposition existed). New York was a crucial and influential state and if it had failed to ratify the Constitution we can only speculate as to the consequences.

The Federalist Papers (because of the depth and lucidity of their explanations and the influence of their authors) provide the best source for revealing the clear intent of those who wrote and ratified the Constitution.1 In Federalist Paper #21 Hamilton writes:

There is no method of steering clear of this inconvenience, but by authorizing the national government to raise its own revenues in its own way. Imposts, excises, and, in general, all duties upon articles of consumption,

1 "The opinion of the Federalist has always been considered as of great authority. It is a complete commentary on our Constitution; and is appealed to by all parties in the questions to which that instrument has given birth!' Cohens vs Virginia 6 Wheat 2 (1821).

may be compared to a fluid, which will in time find its level with the means of paying them. The amount to be contributed by each citizen will in a degree be at his own option, and can be regulated by an attention to his resources. The rich may be extravagant, the poor can be frugal; and private oppression may always be avoided by a judicious selection of objects proper for such impositions. If inequalities should arise in some States from duties on particular objects, these will in all probability be counterbalanced by proportional inequalities in other States, from the duties on other objects. In the course of time and things, an equilibrium, as far as it is attainable in so complicated a subject, will be established everywhere. Or, if inequalities should still exist, they would neither be so great in their degree, so uniform in their operation, nor so odious in their appearance, as those which would necessarily spring from quotas upon any scale that can possibly be devised.

It is a signal advantage of taxes on articles of consumption that they contain in their own nature a security against excess. They prescribe their own limit, which cannot be exceeded without defeating the end proposed — that is, an extension of the revenue. When applied to this object, the saying is as just as it is witty that, "in political arithmetic, two and two do not always make four!' If duties are too high, they lessen the consumption; the collection is eluded; and the product to the treasury is not so great as when they are confined within proper and moderate bounds. This forms a complete barrier against any material oppression of the citizens by taxes of this class, and is itself a natural limitation of the power of imposing them.

Impositions of this kind usually fall under the denomination of indirect taxes, and must for a long time constitute the chief part of the revenue raised in this country. Those of the direct kind, which principally relate to land and buildings,2 may admit of a rule of apportionment. Either the value of land, or the number of the people, may serve as a standard. The state of agriculture and the populousness of a country are considered as having a near relation with each other. And, as a rule, for the purpose intended, numbers, in the view of simplicity and certainty, are entitled to a prefer-

1 Here Hamilton clearly reveals that our Founding Fathers related capitation (direct) taxes "principally...to land and buildings (i.e. one's accumulated wealth). Our Founding Fathers did not even conceive of an income tax but obviously thought that any taxes other than those on consumption would be related to wealth, principally real estate. Presumably a tax on "income" is a tax on wealth though, in reality, it is not. An individual with considerable wealth could conceivably liquidate a portion of it in exchange for food, clothing and shelter. Another individual, however, with a lot less wealth might be forced to work in order to supply himself with the funds necessary to buy food, clothing and shelter. Thus, the second citizen might find himself paying more in "income" taxes than he would if a tax were directly related to wealth. This passage by Hamilton proves that our Founding Fathers believed that indirect taxes only applied to articles of consumption, while direct taxes were related to wealth. They never thought they were giving the Federal government authority to tax a citizen's "income", nor his estate at death, nor his right to transfer property during his lifetime since none of these taxes (i.e. income, estate and gift) relate to consumption nor are they imposed equally on all property.

ence. In every country it is an herculean task to obtain a valuation of the land; in a country imperfectly settled and progressive in improvement, the difficulties are increased almost to impracticability. The expense of an accurate valuation is, in all situations, a formidable objection. In a branch of taxation where no limits to the discretion of the government are to be found in the nature of the thing, the establishment of a fixed rule, not incompatible with the end, may be attended with fewer inconveniences than to leave that discretion altogether at large. (Emphasis added)

It is clear from this passage that our Founding Fathers were far more knowledgeable about the nature of taxes than contemporary Americans who make no distinctions whatsoever concerning them. They understood, for example, that direct taxes were not avoidable, that they did not "prescribe their own limit," but were a "branch of taxation where no limits to the discretion of the government are to be found in the nature of the thing." This principle — which was obviously well understood by the statesmen responsible for our Constitution (which is why they included careful restrictions over the Federal government's power to levy direct taxes) — is totally foreign to the mentality of those who now dominate most of America's legislative bodies. America's current state of affairs tragically confirms the taxing principles so well understood, explained, and warned of by Hamilton in this passage.

Government Must Look To Indirect Taxation

In. Federalist Paper #12, Hamilton uses Britain to explain why the new government must look to indirect taxes for the largest part of its revenue and why direct taxes would "yield but scanty supplies". It is also important to note that while in the former quote Hamilton suggests that direct taxes "principally relate to land and buildings", in the following passage he definitely acknowledges that direct taxes also apply to personal property. When he states "...and personal property is too precarious and invisible a fund to be laid hold of in any other way than by the imperceptible agency of taxes on consumption...," he means that the only way the state could conceivably tax the money hidden away in a citizen's strong box (compatible with constitutional rights) is for the state to tax the consumable products that might be purchased with that money.

It is evident from the state of the country, from the habits of the people, from the experience we have had on the point itself that it is impracticable to raise any very considerable sums by direct taxation. Tax laws have in vain been multiplied; new methods to enforce the collection have in vain been tried; the public expectation has been uniformly disappointed, and the treasuries of the States have remained empty. The pop-

ular system of administration inherent in the nature of popular government, coinciding with the real scarcity of money incident to a languid and mutilated state of trade, has hitherto defeated every experiment for extensive collections, and has at length taught the different legislatures the folly of attempting them.

No person acquainted with what happens in other countries will be surprised at this circumstance. In so opulent a nation as that of Britain, where direct taxes from superior wealth must be much more tolerable, and from the vigor of the government, much more practicable than in America, far the greatest part of the national revenue is derived from taxes of the indirect kind, from imposts and from excises. Duties on imported articles form a large branch of this latter description.

In America it is evident that we must a long time depend for the means of revenue chiefly on such duties. In most parts of it excises must be confined within a narrow compass. The genius of the people will ill brook the inquisitive and peremptory spirit of excise laws. The pockets of the farmers, on the other hand, will reluctantly yield but scanty supplies in the unwelcome shape of impositions on their houses and lands; and personal property is too precarious and invisible a fund to be laid hold of in any other way than by the imperceptible agency of taxes on consumption. (Emphasis added)

Many Against Giving Federal Goverment Any Direct Taxing Power

Federalist Paper #30 further demonstrates how hard Hamilton had to work to persuade his contemporaries to give direct taxing powers to the new government. Many of his contemporaries argued that the new government should have powers to levy direct taxes only after requisitions had failed.

The more intelligent adversaries of the new Constitution admit the force of this reasoning; but they qualify their admission by a distinction between what they call internal and external taxation. The former they would reserve to the State governments; the latter, which they explain into commercial imposts, or rather duties on imported artkles, they declare themselves willing to concede to the federal head. This distinction, however, would violate that fundamental maxim of good sense and sound policy, which dictates that every POWER ought to be proportionate to its OBJECT; and would still leave the general government in a kind of tutelage to the State governments, inconsistent with every idea of vigor or efficiency. Who can pretend that commercial imposts are, or would be, alone equal to the present and future-exigencies of the Union?

Let us attend to what would be the effects of this situation in the very first war in which we should happen to be engaged. We will presume, for argument's sake, that the revenue arising from the impost duties answers the purposes of a provision for the public debt and of a peace establishment for the Union. Thus circumstanced, a war breaks out. What would be the

probable conduct of the government in such an emergency? Taught by experience that proper dependence could not be placed on the success of requisitions, unable by its own authority to lay hold of fresh resources, and urged by considerations of national danger, would it not be driven to the expedient of diverting the funds already appropriated from their proper objects to the defense of the State? It is not easy to see how a step of this kind could be avoided; and if it should be taken, it is evident that it would prove the destruction of public credit at the very moment that it was becoming essential to the public safety. To imagine that at such a crisis credit might be dispensed with would be the extreme of infatuation. In the modern system of war, nations the most wealthy are obliged to have recourse to large loans. A country so little opulent as ours must feel this necessity in a much stronger degree. But who would lend to a government that prefaced its overtures for borrowing by an act which demonstrated that no reliance could be placed on the steadiness of its measures for pay' ing? The loans it might be able to procure would be as limited in their extent as burdensome in their conditions. They would be made upon the same principles that usurers commonly lend to bankrupt and fraudulent debtors — with a sparing hand and at enormous premiums. (Emphasis added)

This would have been a logical enlargement of the taxing powers written into the Articles of Confederation. The Articles provided for the Federal government to make "requisitions" of funds from the various states, but the Federal government (under the Articles) had no recourse if the states failed to meet their requisitions.3

Apportionment Necessary To Keep States Honest

In Federalist Paper #54, Madison touches on another reason for relating direct taxation to representation. States would be less likely to inflate their population figures (to gain added political representation) since this would also increase their tax burdens if a direct tax were imposed.

1A requisition was a specific levy made by the Federal government on the states themselves with each state expected to use its own taxing power to collect the money from its own citizens and was provided for in the Articles of Confederation. The Articles, however, did not give the Federal government any independent taxing powers to collect the tax directly from individual citizens if any state ignored the "requisition". So, giving the new government direct taxing powers to be used if requisitions failed would still be a substantial grant of new taxing power over that contained in the Articles. But, is it logical (considering all the opposition to the proposed new Constitution) that those favoring it would have proposed going from a situation where the Federal government had no independent taxing powers whatsoever to one where it would have the seemingly unlimited power it exercises today?

In one respect, the establishment of a common measure for representation and taxation will have a very salutary effect. As the accuracy of the census to be obtained by the Congress will necessarily depend, in a considerable degree, on the disposition, if not on the co-operation of the States, it is of great importance that the States should feel as little bias as possible to swell or to reduce the amount of their numbers. Were their share of representation alone to be governed by this rule, they would have an interest in exaggerating their inhabitants. Were the rule to decide their share of taxation alone, a contrary temptation would prevail. By extending the rule to both objects, the States will have opposite interests which will control and balance each other and produce the requisite impartiality. (Emphasis added)

Therefore, another important purpose for the apportionment of direct taxes was to keep the states honest in reporting their population for the purpose of Congressional representation and to prevent poorer states from using their votes in Congress to simply drain wealth away from richer states. This they could accomplish by passing taxing bills that would allow their constituents to escape their proportional burden of the tax!4 This, of course, is exactly what has been happening — poorer western and southern states used their disproportionate Congressional power to drain wealth away from richer northern states. Our Founding Fathers put the apportionment provisions into the Constitution to insure that this would not happen — that taxation and representation would go hand-in-hand (regardless of wealth) and that Federal taxation could never be used to redistribute the nation's wealth. But this is precisely how income, estate, and gift taxes are being used today. As a result, the entire country — North and South, rich and poor — is suffering the economic consequences of such an unconstitutional practice.5

4 To see how this was ultimately accomplished, see the words of Representative Hill on page 176.

6 For additional historical references and supporting documentation regarding the constitutional meaning of direct and indirect taxes, see Appendix C.

4

The Federal Government's General Taxing Powers

Up to now we have examined the Federal government's specific constitutional taxing powers. Let us now examine its overall, legitimate taxing powers.

The people turned over general taxing power to the new government so it could achieve certain specific national objectives spelled out in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 1 of the Constitution (see Chapter 2) which limits the U.S. government's use of taxes to three specific areas. The U.S. government can levy taxes:

1. to pay the debts of the United States;

2. to provide for the common defense of the United States; and

3. to provide for the general welfare of the United States.

Note that the first limitation on the government's taxing powers is that it can only tax Americans to pay "the debts of the United States!' It obviously has no constitutional authority to tax Americans to pay anyone else's debts such as those of U.S. corporations (i.e. Chrysler), or of individuals (i.e. FHA mortgage or college loan guarantees), or the debts of individual states, and certainly not those of foreign countries (i.e. the interest on Polish Bonds owed to U.S. banks which was paid by the U.S. government). Government can only lawfully tax Americans to pay the debts of the United States.

The U.S. Constitution simply does not authorize the U.S. government to tax Americans for anything and everything that vote-seeking politicians and free-spending Washington lobbyists want them to pay for. The debts of private citizens and corporations as well as the debts of individual states and foreign governments are not the debts of the United States, and the U.S. Constitution does not give the U.S. government any authority to tax working Americans to pay for such things. All such payments are illegal and a blatant abuse by the U.S. government of its taxing powers.

U.S. Government Not Authorized to Lend Money

This constitutional restriction (allowing the U.S. government to tax Americans only to pay the debts of the United States) is further complemented by another constitutional provision contained in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 2 of the Constitution which states "Congress shall have the power... to borrow money on the credit of The United States." Notice that the Constitution specifically authorizes the Federal government to borrow money, but nowhere does it allow the Federal government to lend money, or to guarantee private or corporate loans or the debts of individual states.

The Constitution also does not allow the U.S. government to tax working Americans for funds to give to a World Bank or an Export-Import Bank to use to finance private, commercial transactions and the grandiose schemes of foreign governments. The U.S. Constitution provides no such grant of power (either express or implied) so all Federal taxes levied for such "banking" purposes obviously represent a clear-cut usurpation of power by the Federal government and are totally illegal and Americans need not submit to it according to Marbury vs. Madison I Cr. 137.

Taxes For The Defense "Of The United States"

The Constitution next grants the Federal government the power to tax Americans "to provide for the common defense of the United States!' Those, therefore, who refuse to pay income taxes because they object to this or that war or because they believe that too much of the nation's budget goes for armaments are on untenable ground. The Federal government has the constitutional authority to tax for these purposes. One might object to such expenditures as wasteful or even stupid and ill- advised but, at least, they are constitutional! Whether such expenditures are proper is a political question that should be resolved at the ballot box. Americans, however, have no lawful basis for not paying income taxes because they do not like political decisions. It is one thing not to pay income taxes because the law itself does not require it or because the levy is unconstitutional. It is another thing not to pay income taxes because one simply disapproves of the nature or amount of constitutional expenditures.

Americans Not Required to Pay Taxes for Unconstitutional Purposes

It makes greater legal sense for such individuals to stop paying U.S. income taxes because such taxes are raised unconstitutionally for unconstitutional purposes since Americans are legally free to refuse to

pay taxes for purposes not authorized by the Constitution. Ironically, those Americans who have refused to pay U.S. taxes because of antipathy to military spending have generally been enthusiastic supporters of government subsidies to private individuals (euphemistically called "social programs") — thereby supporting illegal government expenditures and objecting to legal ones.

What is the "Defense of the United States"?

There are circumstances when what constitutes "the defense of the United States" can be open to question or interpretation. Can the U.S., for example, tax Americans for the defense of some foreign country? The answer to that is obviously no. However, if the defense of that foreign country is related to the defense of America or for the protection of America's vital interests, then the answer is yes. What should be noted, though, is that in this instance it is not the law that is being "interpreted" but the facts as they apply to the law. The facts can be open to "interpretation" but the law itself must be clear or it is not even law! Every freshman law student knows of the legal principle "void for vagueness" which means that if a law is vague (i.e. open to varied interpretation) "it must be void." If laws (including the Constitution) had to be "interpreted" then those laws (and the Constitution) would be "void for vagueness." The legal profession is continually misleading the public about the court's alleged authority to "interpret" the law. 1 Any such "authority" is nonsense.

The General Welfare

It is, however, a total perversion of this last provision that has enabled the U.S. government to escape every restraint placed upon it by the Constitution. The government — and supporters of more government — have completely misled the public concerning the meaning of the "general welfare" clause of the Constitution. This has enabled the government to invade all areas it wishes to, regardless of what the Constitution has to say about it.

This provision should make clear, however, that the "welfare" intended is the "general welfare" of the nation as a whole and not the "welfare" of specific individuals, specific companies, or specific segments of society no matter how deserving those individuals, companies or segments of society might be.

1 For a fuller discussion of such "interpretation, "see How Anyone Can Stop Paying Income Taxes, pages 148-151.

If the United States, for example, builds a foreign embassy, such an expenditure is obviously for the benefit of all Americans. If the government launches a weather satellite, presumably it is for the benefit of all Americans (though some might benefit more than others from the increased accuracy of weather forecasting). Such expenditures would be constitutionally lawful since they are made for the "general welfare" of all the people.

When the U.S. government (through taxation) takes money away from some and hands it over to others (disguised as "subsidies," "grants," "rent supplements," etc.), such activities are not to "promote the general welfare of the United States" but rather for the specific welfare of some at the expense of others. Of course, such expenditures do promote the welfare of many politicians (and the U.S. bureaucracy) who gain public office by promising to provide benefits (literally stealing the property of some in order to buy votes from others) under the guise of promoting the "general welfare!' Not only are such payments not authorized by the Constitution, they also obviously violate the equal protection clause of that document.

If it is sophistically argued that such "grants," "subsidies," "supplements, " etc. are indeed for the "general welfare of the United States" (when such is obviously not the case) it is because it is possible to argue or attempt to justify just about anything! Spanish inquisitors argued that burning people at the stake saved their souls and was thus in their best interest. All attempts to rationalize farm subsidies and other "entitlement" payments as being for the "general welfare of the United States" fall into this category.

When farm subsidies (paying grown men not to produce) were first introduced it was argued that without such subsidies small farmers would go under, leaving fewer farmers who would then be free to raise farm prices. The hypocrisy of the farm subsidy argument was revealed when Congress refused to end tobacco subsidies. Congressmen in favor of this subsidy argued that eliminating it would force tobacco farmers to grow more tobacco (to make up for the lost subsidy) causing tobacco and cigarette prices to fall which, in turn, would encourage more smokers (cigarettes now being cheaper) and thus cause even more cancer in the long run! Therefore, those lobbying for the continuation of tobacco subsidies argued exactly opposite to those who had proposed agricultural subsidies in the first place — and Congress bought their argument, too!

So we have the spectacle of the U.S. government spending millions on tobacco subsidies and millions trying to persuade Americans not to use the product they are taxed to subsidize. Presumably, subsidizing the spread of cancer is in "the general welfare of the United States!"

To further demonstrate the utter hypocrisy and illegality of such government payments and subsidies, the Supreme Court recently ruled that the Federal government could actually confiscate the home of a Dallas woman to satisfy alleged taxes owed by her late husband though her home was presumably protected by Texas homesteading laws. I get routine calls from individuals telling me that the IRS is trying to seize their homes in payment of back taxes. On the other hand, the Federal government purchased homes for the residents of Love Canal and provides rent subsidies to millions more. So here we have the U.S. government taking homes away from some in order to provide homes and rent supplements for others—all in the guise of doing it for the "general welfare!' Such government activity not only violates the taxing power and equal protection clauses of the Constitution, it also violates all logic, decency, and common sense.

The government has literally forced businesses to close because of IRS liens for back taxes. It also routinely lends money to other businesses (either to expand or to provide start-up capital). Can it be lawful or logical for the government to be able to tax some businesses out of existence in order to get the funds to launch or expand the businesses of others?

A Land of Serfs

When the Constitution was written, serfdom still existed in parts of Europe. It existed in Russia until 1861 and continued within the Hapsburg monarchy as late as 1781. Serfdom was a state of half-freedom with serfs owing the "lord and master" approximately 25 percent of their productivity. Taxation also existed in Europe, but tax paying Europeans were hardly serfs and it was certainly not the intent of America's Founding Fathers to establish serfdom in America under the tutelage of the Federal government. What was the nature of taxation in Europe when Americans gave the government the power to levy direct taxes? Insight into this subject can be found in Smith's The Wealth of Nations:

In all countries a severe inquisition into the circumstances of private persons has been carefully avoided.2

At Hamburgh every inhabitant is obliged to pay to the state, one-fourth per cent, of all that he possesses; and as the wealth of the people of Hamburgh consists principally in stock, this tax may be considered as a tax upon stock. Every man assesses himself5 and, in the presence of the magistrate, puts annually into the public coffer a certain sum of money,

2 Not so in America!

3 See How Anyone Can Stop Paying Income Taxes, pages 13,14 and 107.

which he declares upon oath to be one-fourth per cent, of all that he possesses, but without declaring what it amounts to, or being liable to any examination upon that subject. This tax is generally supposed to be paid with great fidelity. In a small republic, where the people have entire confidence in their magistrates, are convinced of the necessity of the tax for the support of the states, and believe that it will be faithfully applied to that purpose, such conscientious and voluntary payment1' may sometimes be expected. It is not peculiar to the people of Hamburgh. (Emphasis added)

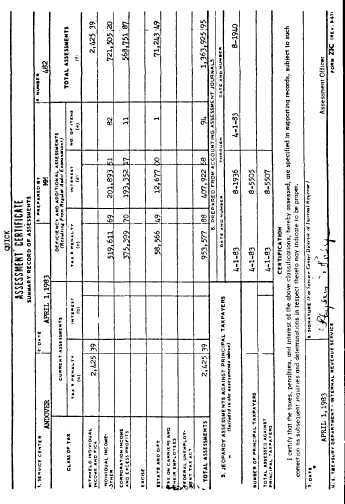

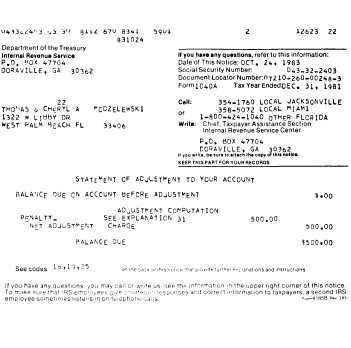

Incredibly, this is how America's current income tax system is also supposed to operate — on the basis of "voluntary payment" and "self-assessment." But most Americans do not know this. The current Internal Revenue Code only allows American citizens to assess themselves and gives the IRS no authority to do so if citizens refuse (see pages 256, 257). Of course the IRS (with the protection of U.S. courts) violates both the law and the principle of self-assessment and collects taxes on the basis of fraudulent and illegal assessments which the government has no authority to make. The IRS then proceeds to enforce payment by deceit, intimidation and extortion — all under the protection of the U.S. Department of Justice and both Federal and States courts!

Note that the good citizens of Hamburgh "volunteered" (under oath) as to what they owed. Note further that they were "not liable to any examination upon that subject." Their sworn statements were considered good enough! Not so for 20th century Americans. Like so many robots, Americans line up and swear under penalty of perjury what they believe (incorrectly) they owe and then submit to exhaustive tax audits, thereby surrendering both 4th and 5th Amendment rights, which expose them to possible prosecution and conviction for tax evasion if their sworn statements are shown to be incorrect! If the U.S. government (as even 19th century Hamburghers must have known) is not going to accept a sworn statement as correct, why bother giving one in the first place?

It is obvious that 20th century Americans (despite all their apparent schooling) do not possess the understanding shown by 19th century Hamburghers. The tax paid by those good citizens of Hamburgh constituted only one quarter of one percent of their assets. Thus a citizen worth $100,000 need only have paid $250. Such citizens could afford to be honest!

4 See Chapter 1 ("Surprise! The Income Tax Is \bluntary!) of How Anyone Can StopPay-ing Income Taxes and pages 242-244 of this book.

How High Should Direct Taxes Be?

The Wealth of Nations, which deeply influenced Amerka's Founding Fathers, comments thusly:

In Holland, soon after the exaltation of the late prince of Orange to the stadtholdership, a tax of two per cent, or the fiftieth penny, as it was called, was imposed upon the whole substance of every citizen. Every citizen assessed himself and paid his tax in the same manner as at Hamburgh; and it was in general supposed to have been paid with great fidelity. The people had at that time the greatest affection for their new government, which they had just established by a general insurrection. The tax was to be paid but once; in order to relieve the state in a particular exigency. It was, indeed, too heavy to be permanent. In a country where the market rate of interest seldom exceeds three per cent, a tax of two per cent, amounts to thirteen shillings and fourpence in the pound upon the highest neat revenue which is commonly drawn from stock. It is a tax which very few people could pay without encroaching more or less upon their capitals. In a particular exigency the people may, from great public zeal, make a great effort, and give up even apart of their capital, in order to relieve the state. But it is impossible that they should continue to do so for any considerable time; and if they did, the tax would soon ruin them so completely as to render them altogether incapable of supporting the state. (Emphasis added)

A tax of 2 percent on capital was believed by Smith to be "too heavy to be permanent." Moreover, a tax of $2,000 paid by an individual worth $100,000 was believed to be so heavy a tax burden that it could not continue "for any considerable time" and would "ruin taxpayers so completely as to render them altogether incapable of supporting the state? This, of course, is exactly what is happening to America today. Smith believed a tax of $2,000 paid by a person with $100,000 was too severe to be permanent, yet many Americans today pay $5,000 in income taxes when they do not have $15,000 to their name. That's more than one-third of their worth! Some people actually have to borrow money in order to pay income taxes.

When the framers of the Constitution thought of direct taxes (as opposed to "duties," "imposts," and "excises") they were obviously thinking of a direct tax that might take from one quarter to perhaps two percent of an individual's capital. They certainly did not envision a type of direct tax that would take away more from Americans than what was taken from serfs by their lord and master — or more than the total wealth they possessed!

U.S. Government Now Presumes to Own All Private Wealth

From time to time the U.S. government releases studies purporting to show how much revenue it loses because of certain tax exemptions and deductions. These studies invariably show how much the government (theoretically) "loses" because of interest, medical or charitable deductions, personal exemptions, etc. All such studies reflect the thinking that any money the government does not take in taxes it has theoretically lostl In essence, this philosophy reflects the thinking that any money taxpayers get to keep for themselves has somehow been given to them by a charitable government. Such reasoning could justify requiring citizens to send in all their money to the government — with the government returning whatever it thinks the citizen deserves.

Sadly, our nation has arrived at a situation where (despite Constitutional safeguards to the contrary) working Americans are held in a form of feudal bondage by the U.S. government for the benefit of an illegal, parasitic, Washington-based, bureaucratic complex.5

slndeed, the Federal government has literally established a "slave state," see page 389.

5

What The U.S. Government

And America Are All

About